The Tricky Intersection Between Fantasy Fiction and the Real World

Some suspect that fantasy writers are a lazy lot. We write fantasy so we don’t have to do any research. Even science fiction writers have to make their near future tech porn plausible, right? Writers of historical fiction might as well be historians (and many are.) Meanwhile, we fantasists just spin castles in the air, supported by hummingbird tongues and intoxicants.

Really? Well, you try and build a world out of nothing and see how far you get.

Magical systems need to be well thought out, coherent, and consistent. The reader needs to know the rules, which means the writer needs to know them first. And, of course, magic must have limits. No limits—no conflict and no story.

But it’s not all about magic.

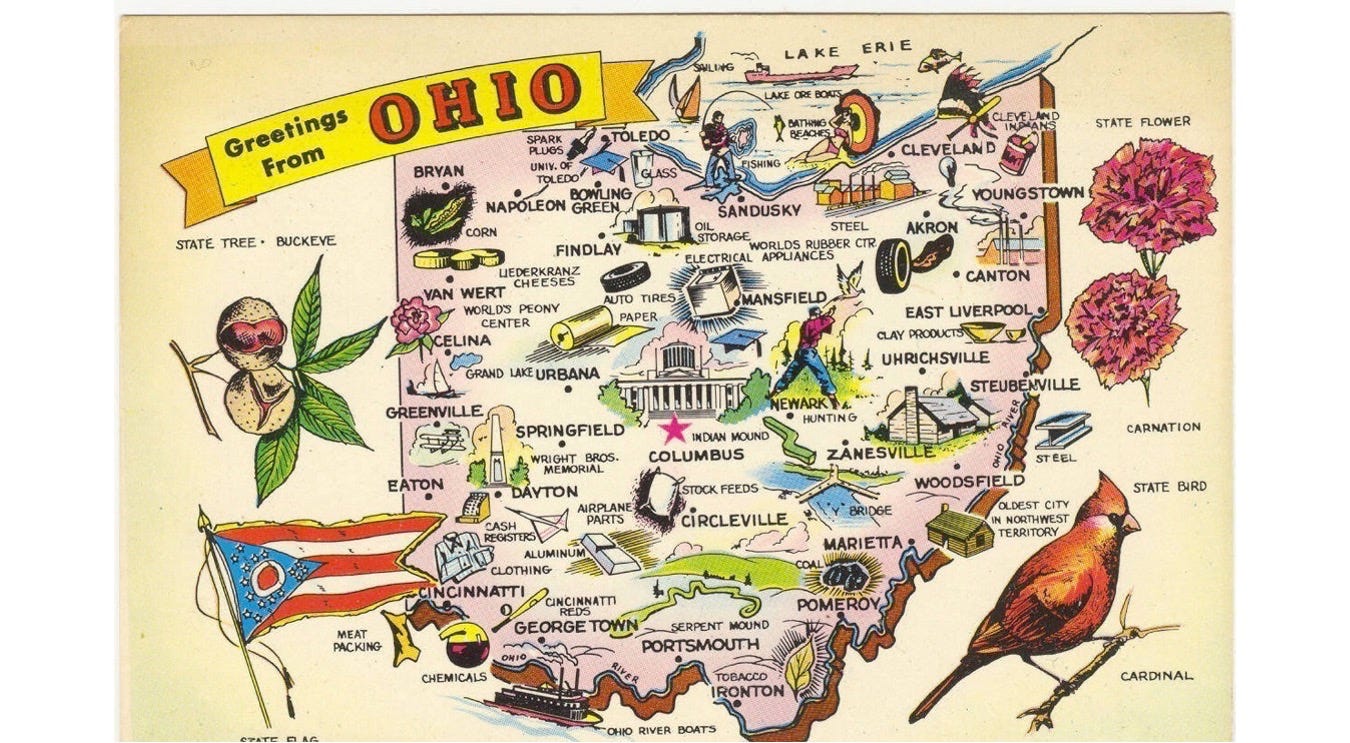

My first series, the Heir Chronicles, was set in the magical world of contemporary Ohio. (This may be my unique contribution to fantasy world-building.) Not only did I have to conform to the actual language and geography of Ohio, I knew that if I messed up, I was likely to get emails from irate residents.

Dear Ms. Chima, please be aware that I just went to Cedar Point and they tore down that wooden roller coaster last year. Keep up.

I also had to explain to bewildered New Yorkers where Ohio is.

Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings and George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire were set in rich, fictional worlds with more than a handshake relationship with medieval Northern European realms. That history provided a sturdy foundation for world-building. In fact, it wasn’t until I read more of the foundational texts of Norse mythology that I realized how much both Tolkien and Martin drew from that tradition. (Winter is coming, anyone?)

Fantasy writers borrow tropes and iconic characters from each other, too, whether we’re aware of it or not. Tolkien’s elves and dwarves resurface over and over in fantasy literature. The bearded hermit wizard mentor connects the nascent “chosen one” with their destiny (LOTR, Eragon, Harry Potter.) I burrowed into Martin’s Seven Kingdoms and somehow emerged with Seven Realms of my own. Something magical about the number ‘seven.’

The Seven Realms and the Shattered Realms books are set in a fictional medieval high fantasy setting. I knew I wouldn’t get complaints from actual residents of that world, but I still had to get the details right.

The key to transporting readers to a fictional world is by convincing them that they’re in good hands through specificity, authenticity, and detail. And that takes research. You need to nail the technology, whether it’s castle architecture, medieval weapons manufacturing, or animal husbandry. Specificity is charming to those in the know if you get it right, but perilous in the execution. It may suit your story to have your character mount his non-magical horse and ride nonstop two hundred miles to the border, but in the process, you will leave all the horse people behind. Get weaponry and battle tactics wrong, and you may hear from the Conservative Sword-Fighting Club (I am not making this up.)

If you’re a fantasist embarking on secondary world-building, you may benefit from a list of world-building questions from author Patricia Wrede. Find them here

https://pcwrede.com/pcw-wp/fantasy-worldbuilding-questions/

Just be wary of trying to answer ALL the questions. Information should be delivered to the reader on a needs-to-know basis. Otherwise, your reader will be hacking through a thicket of words. Provide the framework, and the reader will take it from there.

Runestone Saga is my first series rooted in a specific tradition (Norse mythology), a period in history (the Viking Age), and a geographic region (greater Scandinavia.)

My bookmark folders and hard drive are bulging with references about daily life in the Viking Age. For instance, the climate limited what crops and livestock could be grown, and that in turn affected daily diet, life on small farms, and commerce. Thus my characters eat barley porridge, not wheat bread, and they drink fruit wine and mead because the climate wasn’t suitable for growing wheat or grapes.

I’ve posted previously about the importance of home-based textile production in the economy of the Viking Age https://substack.com/@cindachima/p-140307128 . In my stories and through my characters, I try to convey the value of a simple linen shirt, and the cost in terms of time and labor to replace it if it is lost or destroyed.

All of my novels seem to involve ships and sailing, from the sailboats on Lake Erie to pirates of the Shattered Realms to the coasters of my current series. But by setting these stories in the Viking world, it was important to honor the techniques used by Viking shipbuilders that made their shallow-draft, nimble ships so well-suited for coastal raiding and conquest.

My fantasy worlds swarm with healers and hedge witches who challenge the often male-controlled power structures of the realms. When it comes to remedies and magical herbs, I try to stick as closely to tradition as possible, e.g. using willow bark or syrup of poppy to relieve pain. When reality falls short, I make something up. For instance, “maidenweed” was used as a contraceptive in the Seven Realms series. This stumped the German translator, who reached out, explaining that she couldn’t find anything like that in her dictionaries.

I often make up poisons, too. In that way, I can control dosage, symptoms, and time to onset. Sometimes a character has a use for “two-step lily” (two steps and you’re down.) It also keeps me off the internets, should anyone deep dive into my online search history.

In short, writing fantasy fiction requires more research than you might think. Because, of course, the elements of magic that set fantasy apart are embedded like jewels in the firmament of the real world. Stray too far from that foundation, and readers will wander away confused or ditch your story in disgust. Fantasy writers, like all writers, take real life and “change it up.” We just have a few more options.

Next: the challenge of language in fantasy fiction