The Dabbler's Guide to Fantasy Languages

My first fantasy series, The Heir Chronicles, was set in contemporary Ohio, where I was brought up, so I had a fair mastery of the regional dialect. I tried to keep popular culture at arm’s length, so I wouldn’t be challenged by constantly changing popular slang. (To be honest, popular culture tends to keep ME at arm’s length.)

Still, I had need of terms for magical tools and magical business. For that, I drew on Latin roots and an English-Old English dictionary, reflecting the origins of the magical guilds in Anglo-Saxon England. For example, in Old English, Dyrne means “secret” and sefa means “mind” or “heart.” Thus, dyrne sefa means “secret heart” in my stories, that is, the inborn magical stone that sets the gifted apart. Similarly, gefyllan de sefa means “heart killer,” something that destroys magical ability.

Like I said. Dabbler.

The use of familiar Latin roots can connect a made-up magical word more firmly to its meaning. The master of that was J.K. Rowling, who used that trick both for character names and magical terms. Severus Snape conveys an image and a personality before we ever meet him. Rowling attributes the “Latin-ish” sound of her spells to her classical training. Hence, “lumos” is a spell used to cast light. Word and meaning seem connected because of its ties to the Latin word “lumen,” and our familiarity with words like luminous, luminary, illuminate. Similarly, the meaning of the spell petrificus totalus is easy to figure out—it immobilizes. Her spells that don’t have Latin roots are not so intuitive. Avada kadavra is from the Aramaic language, meaning “let the thing be destroyed.” I will say that “kadavra” hits the ear like “cadaver.”

When it came to developing fantasy languages, Tolkien had a leg up, being a philologist of ancient Germanic languages. His secret passion was inventing languages of his own. In fact, he said that “the 'stories' were made rather to provide a world for the languages than the reverse.” He claimed that he would have preferred to write in Elvish. (He did start out by borrowing Norse names from the Voluspa for his dwarves in the Hobbit.)

If I’d had to invent an entire language in order to publish secondary world fantasy, the primary world would still be waiting for my debut. So I mostly just embroidered around the edges with just-in-time creation or appropriation of fantasy terminology.

In my Seven Realms and Shattered Realms series, both the tribal Spirit Clans and the wizards had their own secrets and their own need for some private terminology. Magic, however, is largely elemental—energy stored in amulets that allow the gifted to accumulate enough to do spectacular things. There is little need for complicated spellcasting. Point and shoot is more like it.

The most prominent example of fantasy language was in the slang used by street thief Han Alister and other members of the street gangs that roved the capital city. For that, I borrowed liberally from thieves’ cant--the slang language of rogues in Georgian London. My best source was Stephen Hart, who has drawn from several sources of the rhyming lexicon and posted a searchable database online. The category headings will give you an idea as to topics covered: Animals, Body, Clothing, Crime, Death, Disease, Entertainment, Rogues, Sex, Violence, and so on. He has also published a book that is available in print and digitally.

Over the course of the books in my realms series, Alister’s voice and word choices change as he leaves the streets behind and develops some upper-class shine. My use of this “patter flash” also allowed my characters to get into authentic criminal situations without arousing the attention of book gatekeepers. Who knew that ‘blue ruin’ referred to gin, slide-hand to pick-pocketing, or that ‘gutter-swiving’ meant doing the carnal deed in the gutter?

You can find a table of thieves’ slang used in the Seven Realms here

Runestone Saga—Stubbing my Toe on a Dead Language

Runestone Saga is based in the traditions of Norse mythology, set in Scandinavia during the Viking Age. That presents its own challenges, being a real tradition in a real place at a real time in history when there was no written language in common use.

The Voluspa is the foundational literature of Norse mythology, but it was an oral tradition handed down through generations. It was first written down by Christians long after the conversion of Scandinavia. In other words, we can thank Christian scholars for what we know about the Norse pantheon, their enemies and allies, and the worlds they inhabited. Given that provenance, it stands to reason that it is short on detail. Events take place in specific named locations (Ithavoll, Vigrid, Jotunheim, Asgard) but those locations are not found on modern maps of Scandinavia. That makes sense, because the Voluspa ends in Ragnarok, the destruction of the nine worlds.

Runestone Saga is set in the time after Ragnarok, when humans share the realm of Midgard (the Midlands) with the other survivors of the apocalypse. It would stand to reason that my characters would have Norse names and speak some variation of Old Norse.

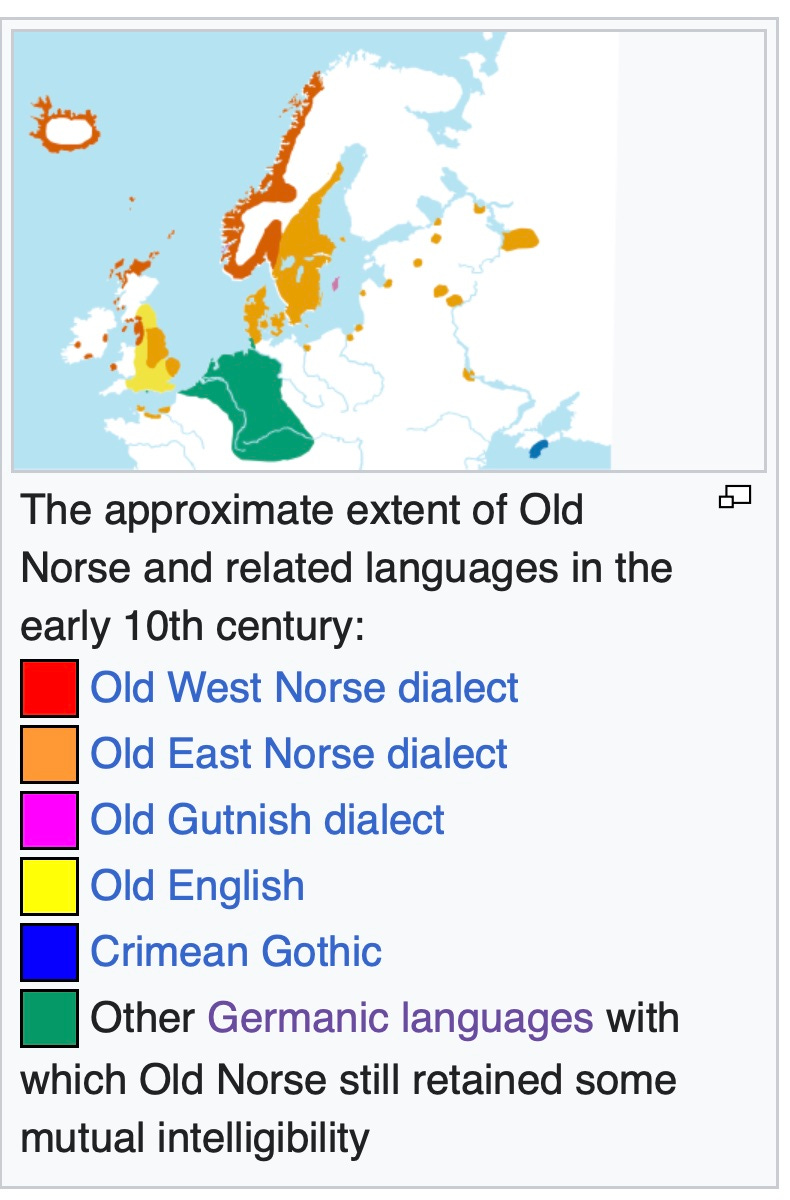

Old Norse was spoken by residents of Scandinavia and their overseas settlements, and coincides in time with the Viking Age, extending through the Christian conversion of Scandinavia, a period from the 8th to the 15thcenturies. Like Old English, it is related to North Germanic dialects, and it is said that Old English and Old Norse were close enough to be mutually understandable at the time of the Danish invasion of the British Isles. Middle English and Early Scots were further influenced by Old Norse, especially within the Viking-occupied Danelaw.

The influence of Old Norse extended as far and wide as the Vikings ranged, from Greenland in the west to the Baltic (Kievan Rus.) During the 11th century, Old Norse was the most widely spoken European language.

But there are no contemporary speakers of the Viking language, just as nobody speaks Old English. It lives on in the way that other medieval languages persist, in descendant languages. The lingual descendants of Old Norse include Danish, Swedish, Norwegian, Icelandic, and Faroese. Of these, Icelandic has remained closest to its roots in Old Norse. Icelandic speakers can read Old Norse, but pronunciation has changed greatly from the original language.

In Runestone Saga, along with researching daily life, ship-building, weaponry, and so on, I’ve drawn my character names from those in use during the period, and used English-Old Norse dictionaries to salt in Old Norse terminology.

The greatest challenge came from the audiobook producers. My editor reached out and said, “The voice actor has a few queries about the pronunciation of words in the book.”

Three hundred and forty queries, to be exact.

I did the best I could, using a variety of online resources to make my best guess. I apologize in advance for any errors. If you scold me, please do so in Old Norse.

References Relating to Fantasy Languages

Bosworth-Toller’s English-Old English dictionary https://bosworthtoller.com

A dictionary of thieves’ cant https://www.pascalbonenfant.com/18c/cant/

Old Norse Resources

https://oldnorse.org/what-is-old-norse/

https://oldnorse.org/how-to-learn-old-norse/

https://oldnorse.org/2020/09/06/the-old-norse-dictionary/

https://www.yorku.ca/inpar/language/English-Old_Norse.pdf

https://cleasby-vigfusson-dictionary.vercel.app

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Old_Norse

https://jacksonwcrawford.com

Jackson Crawford has a PhD in Scandinavian studies from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. For years, he was on faculty at UCLA, UC Berkeley, and the University of Colorado. Now he is a full time public educator and Old Norse language and runes consultant. Offers classes, videos, and books on the topic.

If I could go back and get my doctorate it would absolutely be language-based. I find etymology fascinating. It's one of the (many) reasons I respect Tolkien so much. I'm also really interested in language extinction (although I feel not enough other people are). When I was doing research for my novel and was living in Oaxaca with a group of other NEH scholars, we met an indigenous language speaker who was down to 4 people who could still speak their language and one of the 4 had terminal cancer. It makes me want to be sick and cry at the same time. Once a language like that dies, so does any ability to access and preserve their history and culture. It surprises me that more people aren't up in arms about the problem. It's nice that Old Norse and other languages like Old English survived with sufficient oral/written record that it's not all lost to us - can you imagine the tragedy of a loss of that magnitude? Okay, off the soapbox. Can't wait for book 2 🙂🙂

I love "If you scold me, please do so in Old Norse."! That's so funny 😄