The Connection Between Weaving, Spinning, and Sorcery in the Viking Age

In a previous post, I discussed how my interest in spinning and weaving developed, and reviewed some of the tools and techniques used in fiber arts in the Viking Age. But, wait, there’s more! Through history, the fiber arts were thought to have a strong connection to magic. Weaving and spinning have long been associated with prophesy, fate, and magic in the hands of women.

Spinning and Weaving and the Fates

In Slavic mythology, the Suditse were three female spirits who appeared on the third day after a baby was born and negotiated over the baby’s fate. One was death, the second dealt with misfortunes, and the third handled happiness and prosperity. It was customary to offer gifts to these spirits on the third day after a baby was born in hopes of producing a positive destiny.

The Moirae (fates) of Greek mythology were three sisters who spun, measured, and cut the threads of life: Clotho, the spinner, Lacheses, the alloter, and Atropos, for Death. Destiny was symbolized by a thread spun from a spindle that extended through life.

Their Roman equivalent of the Moirae were the Parcae--Nona, the spinner of thread from distaff to spindle, Decima, who measures the thread, and Morta, who cuts the thread.

In Norse mythology, the Norns are three powerful Jotun women who tend Yggdrasill, the great ash tree at the center of the cosmos. But tree-tending was only part of their job. The Norns spun and possibly wove the web of fate. In that, as in other mythological traditions, they were more powerful than the gods, who had to submit to the fates woven for them.

The Norns are described in the Voluspa, the foundational text of North mythology, this way:

20. Thence come the maidens

mighty in wisdom,

Three from the dwelling

down 'neath the tree;

Urth is one named,

Verthandi the next,--

On the wood they scored,--

and Skuld the third.

Laws they made there,

and life allotted

To the sons of men,

and set their fates.

Norse Sorceresses—the Volur

Sorceresses (the Volur) in Viking Age Europe wielded a type of magic called seidr. The word seidr means “cord” “string” or “snare” in Old Norse.

These so-called “staff-bearers” used a tool akin to a spinning distaff to control and direct magic. The magical practice of women in the Viking age included prophesy, healing, weather-work, mind manipulation, poisons and potions, curses, and shape-shifting. They were often called in during times of famine or war to foretell or manipulate the future.

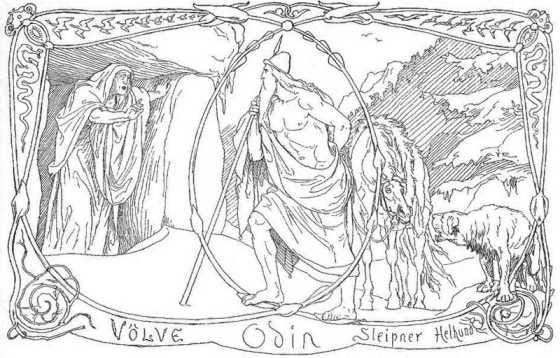

Even the gods consulted the volur when they needed counsel. In one of the foundational texts of Norse mythology, the Voluspa, Odin raises a dead volva, who foretells Ragnarok, the end of the world.

The sagas also contained accounts of the volur being called in to advise rulers during times of crisis. In the Saga of Eirik the Red, a volva known as Thorbjorg is invited to offer counsel in a time of famine in Greenland. This is how Thorbjorg was described:

Now, when she came in the evening, accompanied by the man who had been sent to meet her, she was dressed in such wise that she had a blue mantle over her, with strings for the neck, and it was inlaid with gems quite down to the skirt. On her neck she had glass beads. On her head she had a black hood of lambskin, lined with ermine. A staff she had in her hand, with a knob thereon; it was ornamented with brass, and inlaid with gems round about the knob.

There follows a description of a ritual involving magical singing (vardlokkur) intended to call the spirits of the dead closer to provide prophesy.

It might have been the tie to “women’s work,” i.e. textiles, but it was considered unseemly for a man to perform sorcery or foretell the future. Odin Allfather, ruler of the gods of Asgard, had a thirst for knowledge that drove him to violate that taboo. He learned sorcery from Freyja, one of the Vanir goddesses. He hung himself from Yggdrasil, the tree of life, for nine days in a shamanic ritual to prove himself worthy of learning the runes, magical symbols used by the Norns. His knowledge of runecraft and sorcery made him the most powerful among the gods. Still, in Lokasenna, Loki taunts Odin for his unmanly use of magic.

But people say that you

practiced womanly magic

on Samsey, dressed as a woman

You lived as a witch

Among the humans--

And I call that a pervert’s way of living.

Runestone Saga is is set in the Midlands (Midgard) after Ragnarok, where practitioners of magic are called spinners. Despite their role as healers and counselors, they are the targets of suspicion and abuse. When Liv Halvorsen’s practice of sorcery makes her a target, her brother Eric questions the value of magic and begs her to be more discreet. This is not well-received.

“The web is not off the loom yet,” Liv insisted. “What if you could unravel bits of it and reweave it? What if you could add a bit of lace or a new color? What if you could take something drab and make it beautiful? What if you could see the future and avoid trouble that is coming your way?”

“If you can do magic, then conjure up a sack of gold we can use to pay off the Knudsens,” Eiric shouted, his rage and helplessness driving him. He paused, calmed himself with an effort, then added, softly, “All I’m saying is that there are no miracles any more. The gods are not walking among us, pitching in now and then. We are not going to be saved by magic or anything else.”

“Give up on magic if you want,” Liv said, in a voice like spun steel. “If men give up sorcery, they still rule the world. They sit on the councils, they make the laws, they sail away and make their fortunes or die. Their lives go on much the same.” She snatched up her distaff, the one she used to spin flax, and shook it in his face. “That is why magic is so often the province of women. It is the power we wield in the world, our ability to shape and change and control it. We would be foolish to give it up.”

Evidence of Magical Practitioners in Viking Burials

In the time of the Vikings and throughout the Sagas, female magical practitioners were honored and valued, both for foretelling the future and shaping it, often using tools familiar from fiber arts. After death, they were buried with regalia and grave goods otherwise reserved for great warriors, chieftains, and kings. Some were buried with their staffs and other magical tools and objects that might be of use in the afterlife.

Metal and wooden staffs have been found in dozens of graves of Norse women. Early on, some archaeologists speculated that they might be cooking spits, or some sort of measuring device. Other researchers have pointed out the resemblance of many of the burial staffs to the distaff used to hold fiber while spinning.

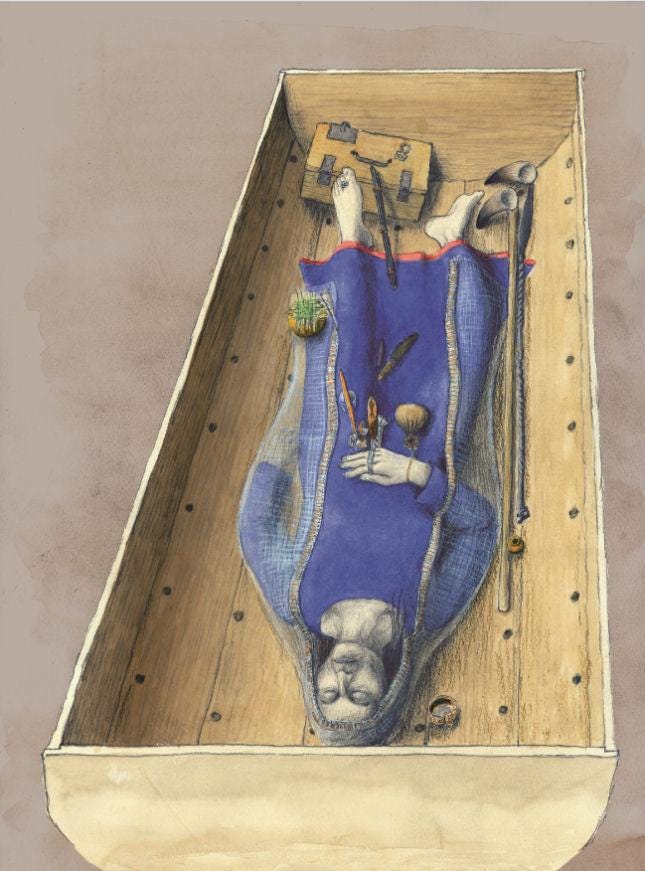

At the ancient Viking ring fort at Fyrkat, Denmark, one of the richest burials is that of a probable volva, possibly a counselor to Harald Bluetooth. The body was buried in a wheeled cart, and the grave goods included some unusual items—a box containing owl pellets and small bird and animal bones, a silver amulet resembling a chair, a hollow box brooch that held white lead, a duck-footed pendant often worn by seeresses, and, of course, an iron staff with bronze fittings.

The two women buried in the Oseberg ship burial may also have been seeresses. They were obviously women of high status, and the grave included two staffs and cannabis seeds.

Grave goods from a volva burial on the island of Oland, Sweden, are displayed at the Swedish History Museum. These include a staff that very clearly resembles a distaff and vessels from distant places.

Finally, Max Dashu presents Seidstaffs of the Volur, multiple images of staffs found in the graves of Norse sorceresses in Sweden, Denmark, and Norway, and compared them to distaffs of various kinds. https://www.suppressedhistories.net/articles2/volur.html

The connection between spinning and weaving and supernatural power in the Viking age may have reflected the importance of fiberwork in Viking Age society. Domestic spinners and weavers produced the sails that propelled Viking ships across the oceans for trade and warfare long before other Europeans made the attempt. They made the home goods and clothing that kept farmers, fishers, warriors and explorers warm and dry through the worst weather in the world. These tasks pretty much remained the province of women until production moved out of the household and into more industrial settings.

The Viking Answer Lady website offers a useful overview of Norse magical practice and the important role of women. She says, “From the time of the ancient Germanic tribes, women were revered by the Northern peoples as being holy, imbued with magical power, and with a special ability to prophecy, a reverence which endured in Scandinavia until the advent of Christianity.” Hmm.

As the Lady says, “The woman of the Viking Age found magic in her spindle and distaff, wove spells in the threads of her family's clothing, and revenged herself on the powerful using the skills of sorcery.”

Resources

The Magic Staffs of the Viking Seeresses, The National Museum of Denmark, https://en.natmus.dk/historical-knowledge/denmark/prehistoric-period-until-1050-ad/the-viking-age/religion-magic-death-and-rituals/the-magic-staffs-of-the-seeresses/

The Viking Sorceress of Fyrkat, http://benedante.blogspot.com/2021/03/the-sorceress-of-fyrkat.html

Grave goods from a seeress buried at the ring fort at Fylkat, National Museum of Denmark https://en.natmus.dk/historical-knowledge/denmark/prehistoric-period-until-1050-ad/the-viking-age/religion-magic-death-and-rituals/a-seeress-from-fyrkat/

The Oseberg ship burial, found in Oseberg Norway. Burial of two wealthy women. https://www.vikingtidsmuseet.no/english/research/gjellestad-ship/oseberg-ship/

Grave goods found in the Oseberg ship burial included two staffs. https://johannawittenberg.com/oseberg-ship-burial/

The Viking Answer Lady: Women and Magic in the Sagas: Seidr and Spa. http://www.vikinganswerlady.com/seidhr.shtml Accessed 5-27-24

Lindow, John, Norse Mythology, A guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals and Beliefs. New York, Oxford University Press, 2001.

McCoy, Daniel, The Viking Spirit, An Introduction to Norse Mythology and Religion, 2016

The Saga of Eirik the Red, 1880 translation into English by J. Sephton from the original Icelandic 'Eiríks saga rauða' available online here https://sagadb.org/eiriks_saga_rauda.en

The Poetic Edda, Stories of the Norse Gods and Heroes, translated and edited by Jackson Crawford, p. 105. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company, 2015

Image Credits

The Norns (1889) by Johannes Gehrts By Johannes Gehrts - Felix Dahn, Therese Dahn, Therese (von Droste-Hülshoff) Dahn, Frau, Therese von Droste-Hülshoff Dahn (1901).Walhall: Germanische Götter- und Heldensagen. Für Alt und Jung am deutschen Herd. Breitkopf und Härtel., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4624295

Odin and Volva image Lorenz Frølich, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Völva,_Odin,_Sleipnir_and_Helhound_by_Frølich.jpg

The buried seeress from Fyrkat – reconstruction drawing by Thomas Hjejle Bredsdorff. https://en.natmus.dk/historical-knowledge/denmark/prehistoric-period-until-1050-ad/the-viking-age/religion-magic-death-and-rituals/a-seeress-from-fyrkat/

Finds from a priestess’s grave from Oland, Sweden in Swedish History Museum By Berig (Own work) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC BY-SA 4.0-3.0-2.5-2.0-1.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0-3.0-2.5-2.0-1.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

This is fantastic!